Practice Review – Revisiting pregabalin: Optimising safety in prescribing for neuropathic pain

Australian GPs recently received a Practice Review on prescribing pregabalin safely. Find out more about how to read your Practice Review.

Here we are revisiting prescribing of pregabalin, including its combination with opioids and benzodiazepines, to raise awareness of potential harmful and hazardous use.1-5 The pregabalin product information and consumer medicine information were recently updated to include a boxed warning highlighting the risk of misuse, abuse and dependence which can lead to overdose and death, especially when used with other CNS depressants.8

Boxed warnings were added following a TGA investigation into continuing Australian reports of misuse associated with pregabalin, and abuse and dependence associated with pregabalin and gabapentin.

This Practice Review is intended to help GPs reflect on their prescribing of pregabalin for neuropathic pain including its combination with opioids and benzodiazepines. It was developed in collaboration with GPs and has been sent to approximately 30,000 prescribers nationally, including all GPs.

The information on this page is provided to help GPs interpret their individual Practice Review data.

Download and print a sample report

Frequently asked questions

Data from across Australia

Further aggregate data (national and by remoteness area) are provided below to complement your individual Practice Review. Where data vary between RAs, data for all five RAs are presented alongside national-level data.

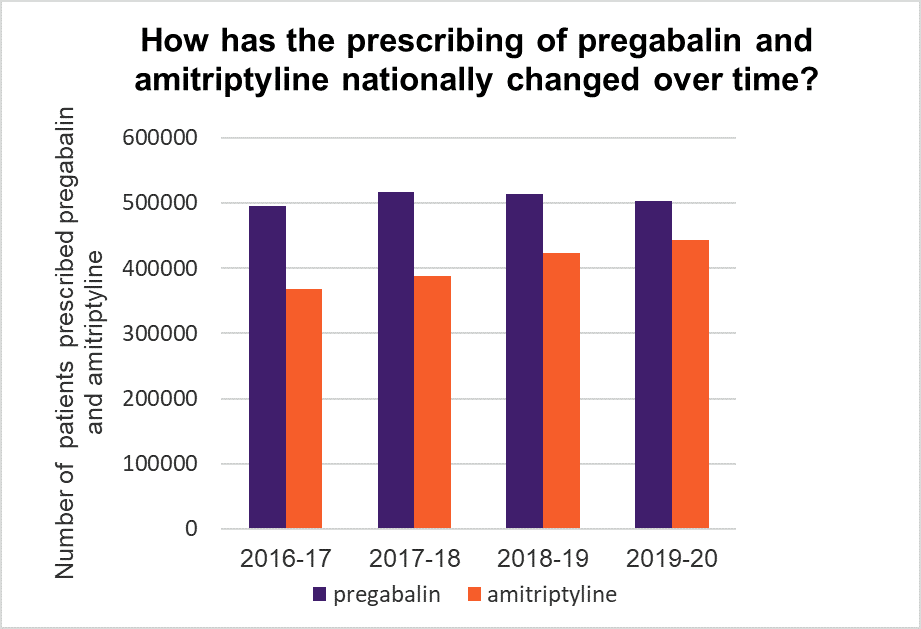

Read an accessible text version of this graph

Points for reflection

- For chronic neuropathic pain consider a TCA (amitriptyline or nortriptyline) or an SNRI (duloxetine or venlafaxine) or a gabapentinoid (pregabalin or gabapentin). Base choice on individual patient factors and medicine properties.15

- Advise patients of common adverse effects,22 and risk of dependency and misuse with pregabalin.5,23 Gabapentinoids (particularly pregabalin), TCAs and SNRIs can worsen mood and cause suicidal thoughts. Assess individual patient risk before prescribing.15

- For acute neuropathic pain, gabapentinoids may be preferred due to their faster onset of action, but their use may be limited by potential harms. Consider a TCA or SNRI if a gabapentinoid is not appropriate.15

- Lidocaine 5% patches are preferred options for patients with localised neuropathic pain, particularly for older or frail patients and those on multiple medicines.15

- Gabapentin, nortriptyline, duloxetine, venlafaxine and lidocaine are not available on the PBS for neuropathic pain.

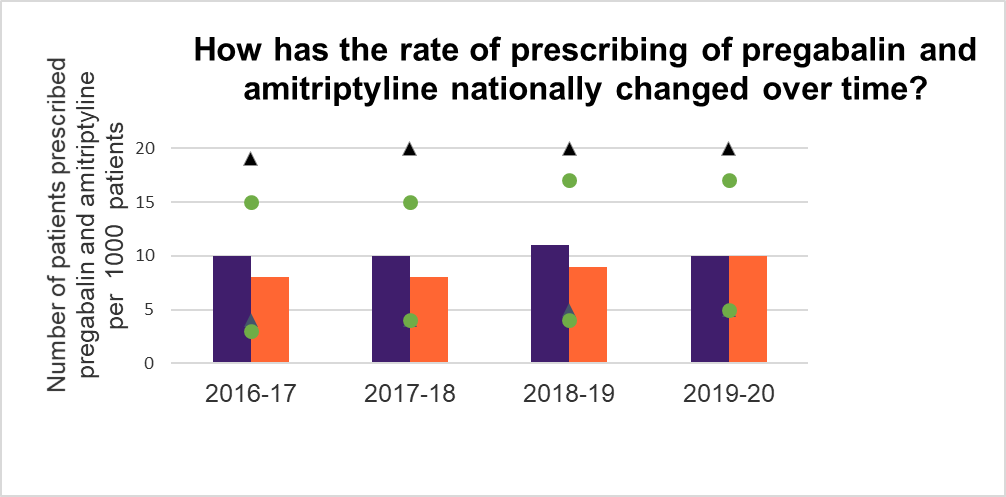

This graph shows the number of unique patients (nationally) dispensed a prescription for pregabalin and/or amitriptyline expressed as a rate per 1000 unique patients who had a Medicare category 1 consultation in that financial year.

See these data broken down by remoteness area (RA)

Read an accessible text version of this graph

Points for reflection

- Take a targeted history and perform a physical examination (including sensory testing) to help determine a probable diagnosis before starting a medicine.19 Consider using a validated screening tool, eg DN420 or painDETECT.15,21

- Do not use imaging solely to confirm diagnosis – reserve it for cases where findings will change management.15

- Do not use pregabalin as a diagnostic tool for neuropathic pain. Approximately eight patients with neuropathic pain need to be treated with pregabalin for one to achieve a 50% reduction in pain not attributable to placebo.15

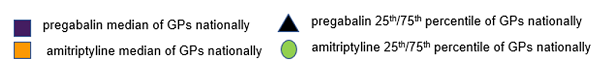

Note: Based on twice-daily dosing, each pack of pregabalin should usually last 28 days.

Read an accessible text version of this graph

Points for reflection

- Start with a low dose, increasing slowly to minimise adverse effects. Benefits should be apparent after around 4 weeks. Continue if effective, and tolerated – if not, consider tapering, then trialling an alternative.15

- Trial deprescribing every 3–6 months to assess ongoing benefits and reduce risk of adverse effects.15

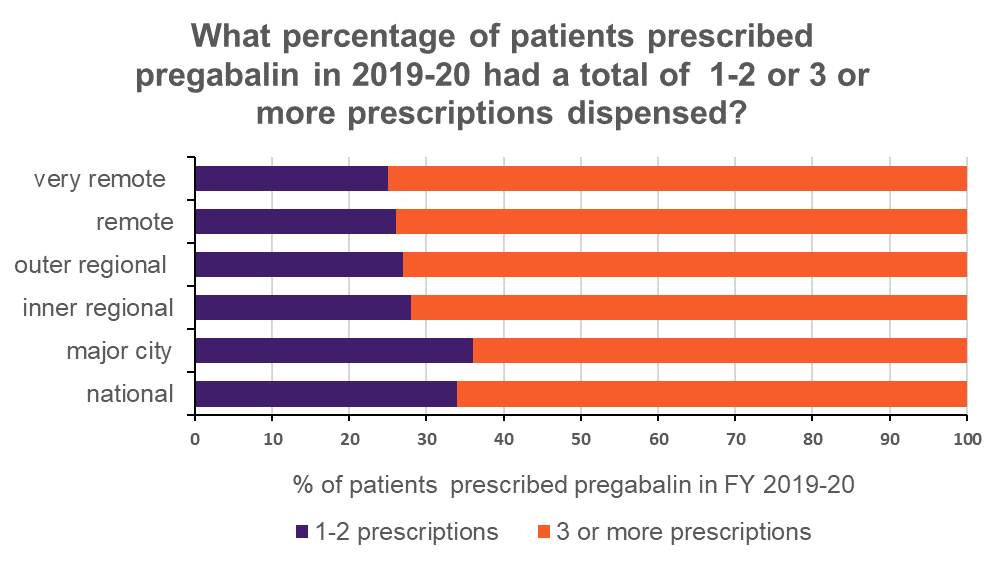

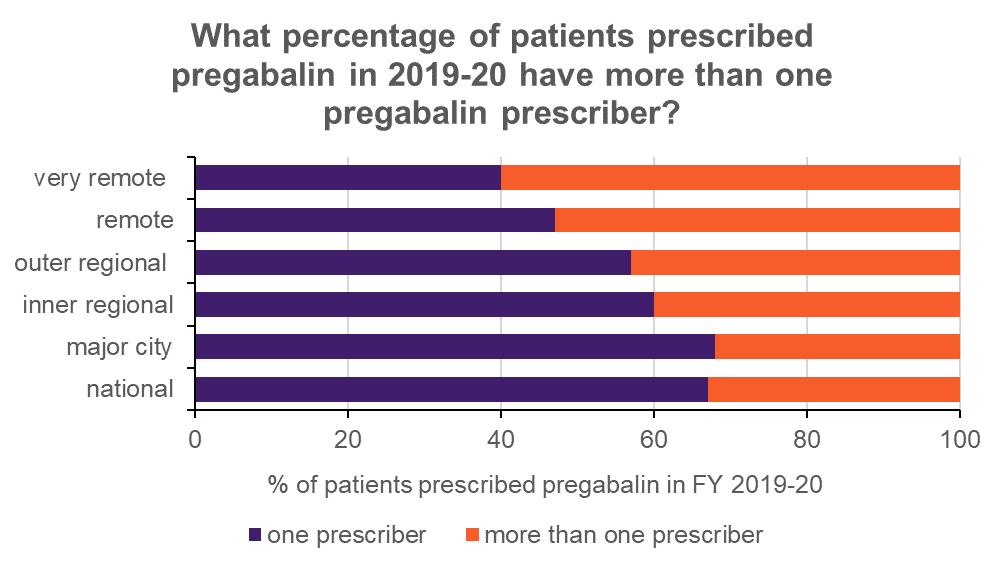

Read an accessible text version of this graph

Points for reflection

- Exercise caution when prescribing pregabalin2 particularly for patients at increased risk of misuse6 eg, those with multiple prescribers.2

- Continue to monitor for signs of tolerance, misuse and/or abuse, such as increase in dose or drug-seeking behaviour.8,24 The introduction of Real Time Prescription Monitoring (RTPM) may help highlight potential medicine misuse.

Note: Medicines may not have been prescribed at the same time. Prescriptions for injectable medicines, as well as those indicated solely for cancer pain, palliative care or dependence, are not included. Due to rounding, percentages do not equal 100%.

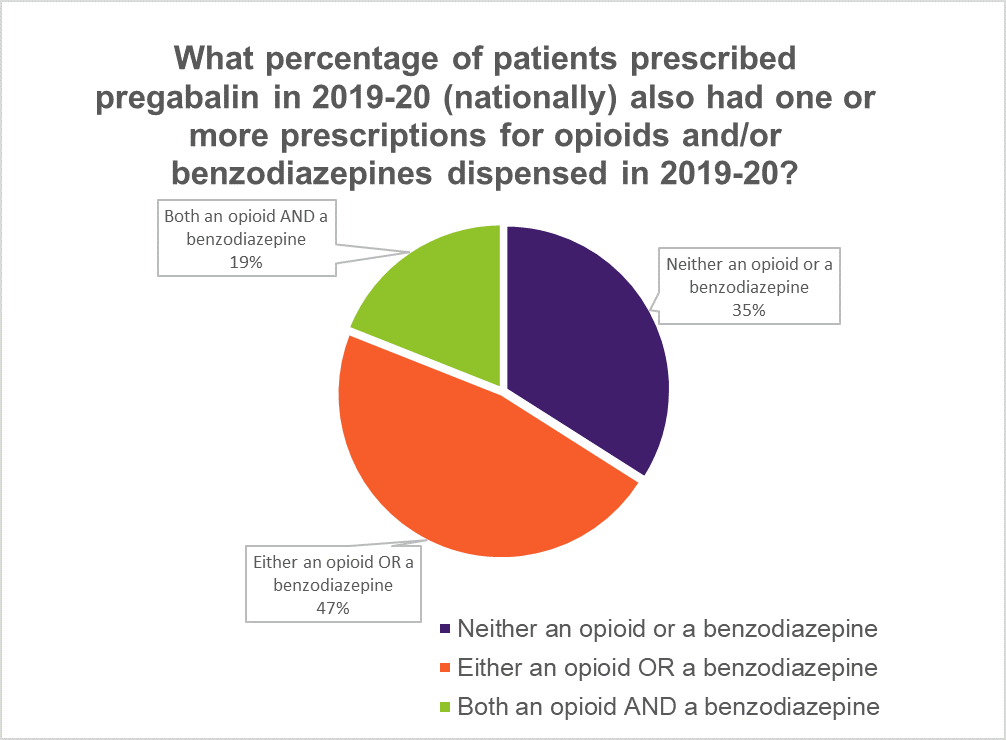

Read an accessible text version of this graph

Points for reflection

- Ask patients what other medicines they are using before you prescribe pregabalin. Explain the significant risks of using pregabalin with medicines such as opioids and benzodiazepines, and with illicit drugs. Tell them to inform any other health professionals they see that they are taking pregabalin.

- Avoid co-prescribing pregabalin with central nervous system depressants if possible.22 Most fatal overdoses involving pregabalin also involve other drugs, predominantly opioids,2,4 benzodiazepines,2,4 alcohol,2,4 illicit drugs2 and antidepressants.4

References

- Australian Government Department of Health Advisory Committee on Medicines. Meeting Statement - Meeting 13, Friday 1 February 2019. Canberra, 2019 (accessed 7 December 2020).

- Cairns R, Schaffer AL, Ryan N, et al. Rising pregabalin use and misuse in Australia: trends in utilization and intentional poisonings. Addiction 2019;114:1026-34.

- Crossin R, Scott D, Arunogiri S, et al. Pregabalin misuse-related ambulance attendances in Victoria, 2012-2017: characteristics of patients and attendances. Med J Aust 2019;210:75-9.

- Hägg S, Jönsson AK, Ahlner J. Current evidence on abuse and misuse of gabapentinoids. Drug Saf 2020:1235-54.

- NPS MedicineWise. Gabapentinoid misuse: an emerging problem. Sydney: NPS MedicineWise, 2018 (accessed 4 December 2020).

- Evoy KE, Sadrameli S, Contreras J, et al. Abuse and misuse of pregabalin and gabapentin: A systematic review update. Drugs 2020.

- Expert Group for Toxicology and Toxinology. Therapeutic Guidelines Pregabalin and gabapentin poisonings West Melbourne: Therapeutic Guidelines Ltd, 2020 (accessed 23 August 2020).

- Pfizer Australia. Pregabalin (Lyrica) product information updated 13 November 2020. West Ryde, NSW: Pfizer Australia, 2011 (accessed 7 December 2020).

- Schaffer AL, Busingye D, Chidwick K, et al. Pregabalin prescribing patterns in Australian general practice, 2012 to 2018. BJGP Open 2021;5: bjgpopen20X101120.

- Filipetto FA, Zipp CP, Coren JS. Potential for pregabalin abuse or diversion after past drug-seeking behavior. J Am Osteopath Assoc 2010;110:605-7.

- PBS Information Management Section, Pricing and PBS Policy Branch, Technology Assessment and Access Division. PBS expenditure and prescriptions report 1 July 2019 to 30 June 2020. Canberra: Australian Government Department of Health, 2020 (accessed 5 January 2021).

- Vinas-Bastart M, Oms-Arias M, Pedraza-Gutierrez A, et al. Clinical use of pregabalin in general practice in Catalonia, Spain: A population-based cross-sectional study. Pain Med 2018;19:1639-49.

- Wettermark B, Brandt L, Kieler H, et al. Pregabalin is increasingly prescribed for neuropathic pain, generalised anxiety disorder and epilepsy but many patients discontinue treatment. Int J Clin Pract 2014;68:104-10.

- Choosing Wisely Australia. Recommendations: Faculty of Pain Medicine, ANZCA. Sydney: Choosing Wisely Australia, 2020 (accessed 17 November 2020).

- Expert Group for Pain and Analgesia. Therapeutic Guidelines: Pain and analgesia. West Melbourne Therapeutic Guidelines Ltd, 2020 (accessed 21 December 2020).

- Derry S, Bell RF, Straube S, et al. Pregabalin for neuropathic pain in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2019;1:CD007076.

- Enke O, New HA, New CH, et al. Anticonvulsants in the treatment of low back pain and lumbar radicular pain: a systematic review and meta-analysis. CMAJ 2018;190:E786-E93.

- Shanthanna H, Gilron I, Rajarathinam M, et al. Benefits and safety of gabapentinoids in chronic low back pain: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. PLoS Med 2017;14:e1002369.

- Haanpää ML, Backonja MM, Bennett MI, et al. Assessment of neuropathic pain in primary care. Am J Med 2009;122:S13-21.

- Bouhassira D, Attal N. Diagnosis and assessment of neuropathic pain: the saga of clinical tools. Pain 2011;152:S74-83.

- Freynhagen R, Baron R, Gockel U, et al. painDETECT: a new screening questionnaire to identify neuropathic components in patients with back pain. Curr Med Res Opin 2006;22:1911-20.

- Australian Medicines Handbook. Neurological drugs. Adelaide: AMH Pty Ltd, 2020 (accessed 17 November 2020).

- NHS England and Public Health England. Advice for prescribers on the risk of misuse of pregabalin and gabapentin. London, UK: Public Health England and NHS England, 2014 (accessed 4 December 2020).

- Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency. Pregabalin (Lyrica), gabapentin (Neurontin) and risk of abuse and dependence: new scheduling requirements from 1 April. London, UK: Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency, 2019 (accessed 2 December 2020).

- Finnerup NB, Attal N, Haroutounian S, et al. Pharmacotherapy for neuropathic pain in adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Neurol 2015;14:162-73.

- Parsons G. Guide to the management of gabapentin misuse. Prescriber 2018;29:25-30.